Tibetan Thangka Painting

Eleven-Headed, Thousand-Armed Avalokiteshvara Central Tibet, mid-12th century

INTRODUCTION

A Tibetan painting is called a Tangka, or Thangka, which means, literally, “something that is rolled-up”. This scroll format is popular for personal devotional works because they can be easily transported, although some thangkas may be so large that they can only be displayed on hillsides.

Large appliqué thangka unrolled on a hillside at Labrang in Amdo, Eastern Tibet, c.1930.

Tibetan Thangka Painting is a highly complex form of religious art whose structures are based on mandalas (mystical diagrams originally drawn on the ground for ritual use). This genre of art grew out of Indian miniatures and cloth paintings, and as it evolved, it developed its own unique cultural style and later began to incorporate influences from Chinese landscape painting.

These paintings are executed by monks or are created by laymen under the supervision of a lama. The artist is bound by a theme, composition, and physical proportions of the figures depicted. It follows, therefore, that he must also be well versed in the sacred texts that explain the spiritual preparation necessary to make a painting. For example, if the painting includes an “after-death plane,” the artist is required to prepare for his own eventual death.

PURPOSE

Ultimately, the goal of the Buddhist is to escape samsara, the cycle of life, death, and rebirth and to put an end to suffering forever by entering the blissful state called nirvana, which exists beyond the physical plane. The function of thangkas is to move practitioners toward a more divine relationship with the world that ultimately will lead to the transcendence of earthly things.

Thangkas contain mystical symbols that plunge into the depths of the human consciousness. They are meditational devices designed for the spiritual advancement of the artist, viewer, and patron. These paintings are commonly hung in temples or at family altars, are carried in religious processions, and are used to illustrate sermons. At times they are dedicated to a sick person, or they are used to remove spiritual or physical obstacles to a particular goal, or to help a deceased person receive a happier rebirth. They are also commissioned for special religious occasions to help the donor gain spiritual merit.

The artist also benefits greatly from the disciplined labor involved in the production of a thangka, and more importantly from the visionary process of art that requires him to see reality on a more metaphysical level.

The purpose of Tibetan art is to effect visual liberation, or liberation through seeing. The path toward freedom can be conveyed through didactic paintings, which are narrative in their approach, but more often, the paintings are of an entirely different nature. Tibetan art uses symbolic forms and images to connect to the psyche of the viewer, in an archetypal (and often quite visceral) manner.

Kalachakra in sexual union with his consort Vishvamata, (detail).

VISUAL LIBERATION

The idea that consciousness can be focused by meditation on external objects is unique to Tibetan Buddhism, and the figures of deities portrayed in thangkas and sculptures are the subjects of contemplation that help one to advance on the spiritual path.

Figures depicted in thangkas may be gods, demons, any one of many Buddhas, gurus (spiritual teachers), or bodhisattvas. A bodhisattva is one who has reached the stage of enlightenment but, rather than continue on to nirvana, chooses to remain on earth in order to help other sentient beings still struggling along the path to awakening.

It is important to understand that all these various mythological and symbolic figures represented in the artworks are all aspects of every human being. The Buddha is seen, therefore, not as a solitary messiah but as an evolutionary principle and a paradigm of what it is possible for human beings to become.

As the myriad deities enter our perception through the artworks, they provide us with the opportunity to recognize them later when they will manifest in an intermediary phase between death and rebirth.

Tibetans believe that in this Bardo state, or “state of becoming,” the consciousness of a human being leaves its physical shell and wanders around in a kind of “no man’s land.” It is thought that during this time, the images of the deities will approach the bodiless consciousness of the dead person, first appearing as peaceful figures and then becoming increasingly wrathful and more violent as the self spirals downward to lower levels of existence. If the dead person does not recognize them as reflections of himself during this time, he will be reborn back into samsara and will not have a chance to achieve nirvana until after his next existence.

Therefore, the paintings are used to help guide the viewer toward spiritual liberation by providing reflections on the nature of reality and visions into what is yet to come. The thangka is viewed not as just an ordinary image but as an evocation. Tibetan paintings are intended to bring archetypal elements out of the psyche. The primary intent is to help both the artist and the viewer reach nirvana through intense meditation. Consequently, the efforts or actions (karma) of the artist are transferred to the viewer. By meditating on these icons, it is possible to elevate one’s self to a higher level of consciousness.

STRUCTURE

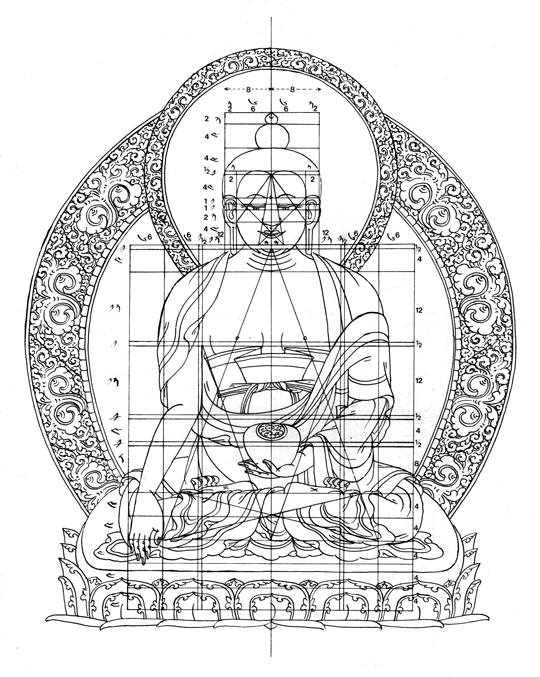

These highly intricate works are also structured upon strict guidelines according to a canonized iconometric system of measurement and proportion, so an advanced technical skill in drawing is essential for their production. Typically, a student of Tibetan art must train as an apprentice in drawing for six years before they are permitted to touch a paintbrush! An example of the classical iconometry for the Medicine Buddha is shown below.

Drawing showing the iconometric proportions of Buddha Sakayamuni,

Beer, R. 1999. The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs. Shambala.

TECHNIQUE

The fabric of a Thangka is prepared by stretching muslin or linen on a frame and treating it with lime slaked in water mixed with yak hide glue. A ground layer, often created with chalk or kaolin (white clay), is added to the sizing solution before application to the support. The surface thickens as it dries and is then burnished with a shell to make it smooth and shiny. The outlines of the figures are first drawn in charcoal and then filled in with color. The paint used consists of powdered pigments, mostly mineral, mixed with a binder of gelatin, a diluted solution of hide glue that is water-soluble and matte in appearance. The predominant colors are lime white, red, arsenic yellow, vitriol green, carmine vermillion, lapis lazuli blue, and indigo. Pure gold is used for backgrounds and for ornamentation.

The painter Tsering and his canvas in the Norbu Lingka, Lhasa, Tibet 1937.